WENATCHEE, WA — Scientists at Washington State University’s Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center (TFREC) are growing fungi that could one day protect apple crops by parasitizing insect pests.

The team of entomologists is testing three different species of fungi, including a strain related to the “zombie” Cordyceps fungus that inspired the show “The Last of Us,” as living pest control agents for codling moth.

“If these fungi are as effective and adapted for our environment as they appear to be, they could become really useful tools,” said Rob Curtiss, Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Entomology.

Codling moth has been a problem for Pacific Northwest fruit growers practically since apples arrived here. The quintessential “worm in the apple,” the moth traveled with the crop from the apple tree’s ancestral homeland in Eurasia.

“It’s been in the U.S. since at least the 1700s,” Curtiss said. “As apples went west, codling moths went with them.”

Once hatched, caterpillars immediately search out an apple, burrow inside, and eat the protein-rich seeds, marring the fruit and halting its growth. There are few effective management tools, and the pest is developing resistance to the viral bio-controls organic growers rely on.

Once hatched, caterpillars immediately search out an apple, burrow inside, and eat the protein-rich seeds, marring the fruit and halting its growth.

“You can forget about managing them when they’re in the apple,” Curtiss said. “Once they’ve gone inside, they’re really protected.”

He established a codling moth colony at TFREC in 2023 using funds from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission and the Washington Commission on Integrated Pest Management. The captive population helps researchers understand the insect’s behavior and test potential control methods.

To capture his guests, Curtiss visited orchards throughout central Washington, wrapping the bases of apple tree trunks in corrugated cardboard.

“For the larvae, it seems like a nice, protected place to pupate,” he said. “Then we come and collect that cardboard and get massive numbers of live codling moths.”

During the rainy fall of 2023, Curtiss and his team hurried to detach pupae from piles of wet cardboard before their cocoons could mold.

“I started to see the occasional dead codling moth that looked like it had been killed by a fungus,” he said.

Curious about what killed these larvae, Curtiss showed his finds to fellow WSU entomologist Tobin Northfield; Northfield and his student César Reyes Corral, who was culturing pathogens of a different fruit pest, leafhopper, offered to grow out fungi from the most promising specimens in hopes of identifying it.

“Stumbling upon these fungi was a lucky strike,” said Reyes Corral, a soon-to-be PhD graduate. “It was a side project that turned into something very exciting.”

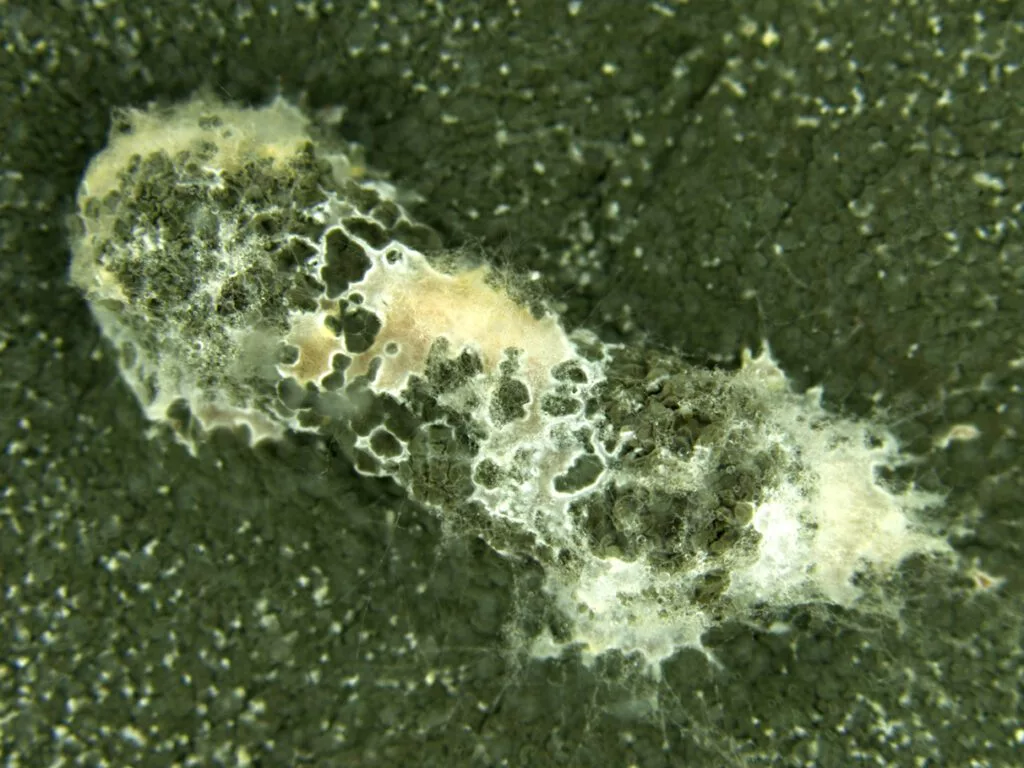

Typically, dead larvae decompose, turning black and gooey. Fungal-infected specimens, in contrast, were white, dry, and crusty, with a powdery residue inside their exoskeletons. Once scientists placed the dead larvae on a petri dish, fungi started to grow.

To identify these fungi, Reyes Corral isolated them, ground them up, and sequenced their genetics, revealing them as strains of Ophiocordyceps, Beauveria, and Metarhizium. The team is now infecting larvae with these fungi to confirm whether they are indeed moth-killers.

In fungal infection, a single spore lands on an insect, then germinates and punctures the larvae’s exoskeleton.

“The insect doesn’t die immediately,” Curtiss said. “It continues to survive while the fungus is growing and using up its resources.”

Once the fungus has depleted its host, it’s ready to reproduce. Under the right environmental conditions, it will send out spores that land in places where other insects encounter them, and the cycle begins again.

From the three specimens, Reyes Corral harvested spores — yellow-white particles from Beauveria, dark green from Metarhizium, pink-white from Ophiocordyceps — for testing.

In their experiments, Curtiss and Reyes Corral will select specimens for optimal fast growth and kill rates, with the goal of developing a WSU strain for commercial production by industry.

“The real value of the project is that it can give apple growers hope,” Curtiss said. The more pest control modes that scientists can give farmers, the better.

“So far, the preliminary data is very exciting,” Reyes Corral added. “I’m sure there’s a future where these and other beneficial fungi are useful for fruit growers.”

New Plant Growth Facility

WSU scientists’ efforts to study insect-parasitizing fungi is a challenge due to the limitations of the center’s aging, 70-year-old growth facility.

“A few degrees Fahrenheit may not seem like much, but for fungi it’s very important,” researcher Cesar Reyes Corral said. “Our existing temperature-controlled rooms where we grow the fungi are really temperature-uncontrolled.”

The university is currently fundraising for a new, modern Plant Growth Facility with state-of-the-art growth chambers and experiment spaces that would benefit this project, among many others.