PORTLAND, OR— In November 2023, Baker City resident Matt Krabacher helped organize a petition pushing to restore a train line that would connect Portland and Salt Lake City.

By the following January, he had raised 1,500 signatures and presented it to the Oregon Legislature. Since then, he’s made it a goal to restore the train line that would connect his rural Oregon town with bigger cities.

The Pioneer was an Amtrak passenger train that operated from 1977 until 1997, when it was cut because of budget shortfalls. It spanned from Seattle to Denver, passing through the Oregon cities of Portland, The Dalles, Pendleton, Baker City and Ontario, as well as Boise and Salt Lake City.

While it hasn’t run for almost three decades, the Federal Railroad Administration in a January report to Congress recommended bringing back the Pioneer route.

Krabacher, the Eastern Oregon vice president for the Association of Oregon Rail and Transit Advocates, joined other regional rail advocates at the Pacific Northwest Rail Summit in Portland on Thursday. He said restoring the line would bring economic opportunity and bridge the gap between rural towns in Oregon, Idaho and Utah.

So what would it take? Largely, funding. Most state transportation funding in Idaho, Oregon and Utah goes to highways, and the states’ transportation departments don’t bring in revenue specifically dedicated to rails. Krabacher said restoring the line doesn’t necessarily mean Amtrak would have to operate the line, but he suggested states create their own rail authority or interstate rail compact.

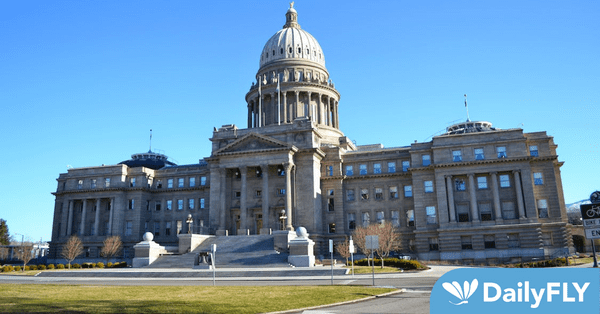

Elaine Clegg, an Amtrak board member and CEO of Boise-based Valley Regional Transit, said restoring the Pioneer line would serve some of the fastest-growing regions in the country.

Idaho experienced the country’s fastest growth in housing units, with a 2.2% increase between 2023 to 2024, followed by Utah at 2%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Oregon’s 0.9% growth in housing units during the same period lagged the national average of 1% as the state struggles to build its way out of a housing crisis.

“It’s true that Amtrak is very focused on the Northeast corridor, as it should be,” Clegg said. “Frankly, there’s a lot of traffic on the Northeast corridor. There’s a lot of infrastructure there, but it should be just as true that Amtrak should be focused on building a national network that truly serves the United States, that truly connects the U.S., and not just parts of it.”

Oregonians who want to take a train east now have few options. The Amtrak Empire Builder, which runs close to the U.S.-Canada border, starts in Seattle or Portland and ends in Chicago. Otherwise, Oregonians would have to take a train south to California to access the California Zephyr, which runs through Salt Lake City and Denver.

There’s also a climate aspect to bringing the line back. Krabacher said the passenger rail, behind waterway transportation, is the most sustainable way to transport people in terms of carbon emissions.

“Many of your children and grandchildren will not be living in the stable climate and stable weather and stable economics that we have enjoyed the past 20 or 30 years, and rail is an added resiliency and added sustainable form of transit that goes a long way to ensuring that our quality of life and access to transit continues for the long term for our region,” he said.

Bringing the train back would bring construction and manufacturing jobs, reduce congestion along Interstate 84 and serve vulnerable populations such as seniors, students and veterans, said Craig Raborn, the executive director of the Community Planning Association of Southwest Idaho, who appeared over video call.

Krabacher said rural Oregon faces a lot of the same struggles as other rural areas, such as aging infrastructure and an aging population with significant health care needs.

The nearest airport is Pendleton, which is a small regional airport, or Boise, which is two hours southeast.

“People in my town are faced with the decision of having to drive hours, which they may not be able to because of their health care needs, or move where the health care is — which most of the people in my town could not afford to do,” he said. “They could afford very easily to take a bus or train to a specialty care facility.”

This story was originally produced by Oregon Capital Chronicle, which is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network which includes Washington State Standard, and is supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity.

Washington State Standard is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Washington State Standard maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Bill Lucia for questions: info@washingtonstatestandard.com.