HEBER CITY, UT – The number of confirmed measles cases in Utah have surpassed 100, with state health officials reporting 102 as of Nov. 25, the last update available from the Thanksgiving holiday week. Of those, 24 were recorded in the last three weeks.

Expecting the state and national measles surge to continue amid low vaccination rates, distrust and some isolating themselves from medical care, Utah health officials are bracing for the outbreak to get worse in coming months.

“I think we actually have more to come before it gets better,” Utah State Epidemiologist Leisha Nolen told Utah News Dispatch on Wednesday.

The largest number of Utah’s confirmed cases are concentrated in Washington County in southwest Utah, where health officials have recorded 74 cases. But last week, the highly contagious virus started spreading in a high school further north, in Wasatch County, with at least eight students confirmed infected.

That outbreak at Wasatch High School “really worries me,” Nolen said.

“That is a new area to be infected. And it’s quite concerning that we suddenly saw so many people with this infection in one school,” she said.

I think we actually have more to come before it gets better.

– Utah State Epidemiologist Leisha Nolen

Wasatch County has some of the lowest public school measles vaccination rates in the state, according to state data.

“So we know that area is vulnerable to a continued spread of measles now that it’s introduced,” she said. “It’s one thing to have it localized in one school, but we know those kids go home, they have siblings at home, and they go do things that expose others. So I am worried that we’re going to have expansion from that in the immediate future.”

The families involved in that outbreak are cooperating and isolating, Nolen said, but because measles is so contagious it’s likely to continue to spread because it took days to recognize the infections. “There were a few days nobody realized it was even measles, (and) they were probably going around while they were infectious,” she said.

Currently, Utah and Arizona are among the states in U.S. with the most recent outbreak cases of measles, according to The New York Times’ tracker. While case counts are slowing in Texas, that state so far has seen the largest outbreak with more than 800 cases, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Meanwhile, for the first time in more than 20 years, the U.S. at the end of the year is poised to lose its elimination status, a long-held designation indicating that outbreaks in the country had been rare and rapidly contained.

As of Nov. 25, a total of 1,798 measles cases have been confirmed in the U.S. across 43 jurisdictions, according to federal health officials. Of those, 12% or 212 have been hospitalized, and three people have died from measles.

In Utah, 11 people have been hospitalized from this year’s outbreak, according to the state’s measles dashboard. “Happily,” Nolen said, “they’ve all been fairly minor and been able to be discharged fairly rapidly.” And the state hasn’t confirmed any deaths from measles.

But Nolen urged Utahns to still take the virus seriously — noting it’s especially dangerous for young children who are unvaccinated or too young to get vaccinated.

Why does Utah and the U.S. have a measles problem?

Many factors are fueling this year’s measles outbreak in and outside of Utah. Nolen said it’s a combination of low vaccination rates, vaccine skepticism in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and distrust in health institutions.

“There’s a lot of misinformation and distrust fueling people’s behaviors and how they make choices, and that is making the outbreak worse,” she said.

There are some similarities to vaccine skepticism stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Nolen noted the measles outbreak is “not at all like COVID” because an effective vaccine has existed for decades and the virus was largely stamped out before vaccination rates began dropping.

Today, most people are vaccinated and protected, but as more parents choose not to vaccinate their children, that puts those kids and others who are immunocompromised at risk.

“I certainly think there’s a lot of factors contributing to why people don’t get vaccinations. Part of it is they don’t know who to trust,” Nolen said. “Certainly these days there’s so many conflicting voices … I understand why they don’t know who to believe. The internet has allowed it so that many voices are very loud, and it’s hard if you aren’t familiar with science or how different systems work to know who to trust.”

Cultural and religious factors have also influenced the spread of measles across the U.S. and in Utah. The outbreak in West Texas earlier this year spread mainly through a large Mennonite community, according to The New York Times.

Utah’s largest hotspot in Washington County, near the Arizona border, has measles cases that can be traced to some areas with a history of polygamy, formerly under control of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a controversial sect that split from the mainstream Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints long ago.

Today, communities including the town of Hildale in Utah and Colorado City, Arizona — an area known as Short Creek — are becoming increasingly ex-FLDS, but vaccination rates are still lagging to effectively protect against measles, the Tucson Sentinel reported.

Distrust of government and medical systems continue to be major drivers in communities with low vaccination rates, Nolen said.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is increase communications with these communities so that we know what they are concerned about and so that we can work with them to help improve their health and make them understand what’s the best way they can do it for themselves,” Nolen said.

Purposeful isolation away from government and health systems could also be resulting in underreported case counts.

Last month, Salt Lake County health officials announced they had identified what was likely the county’s first case of measles — but at the time deemed it “probable” because the patient wasn’t fully cooperating, declining to be tested or participate in disease investigation.

“It’s going to be different in different communities, but I think there are communities that have not just a distrust in government, but they have a distrust of medical systems. And so those people are going to be much less likely to come forward, and so we won’t be able to know how many people are sick in those areas,” Nolen said.

“Other parts of our state, they might not love the government, but they still are very accepting of health care,” she added, “and so they will go forward to their health care providers, and that will help us give a better idea of those areas.”

As a result, Nolen said it’s likely Utah health officials will have a “slightly skewed understanding” of how prevalent measles actually is across the state.

“We have heard from many community members that they know that there are individuals in their community who have symptoms — even the patients believe they have measles, but they don’t go in and get tested,” she said.

“So we know there are a number of people who just stay home and suffer through this illness without getting any medical attention,” Nolen said. “We can’t count those people, so we don’t know how many exist, but we certainly hear from community members that that is happening.”

Nolen said she worries for those people — and especially “kids who don’t have a choice, their parents have chosen whether or not to vaccinate.”

“I’m concerned about them,” she said, in addition to the “people who unfortunately have gotten misinformation and therefore aren’t choosing to protect their families.”

What to know about measles

Unvaccinated people — including children too young to be vaccinated — are more likely to experience severe complications from a measles infection.

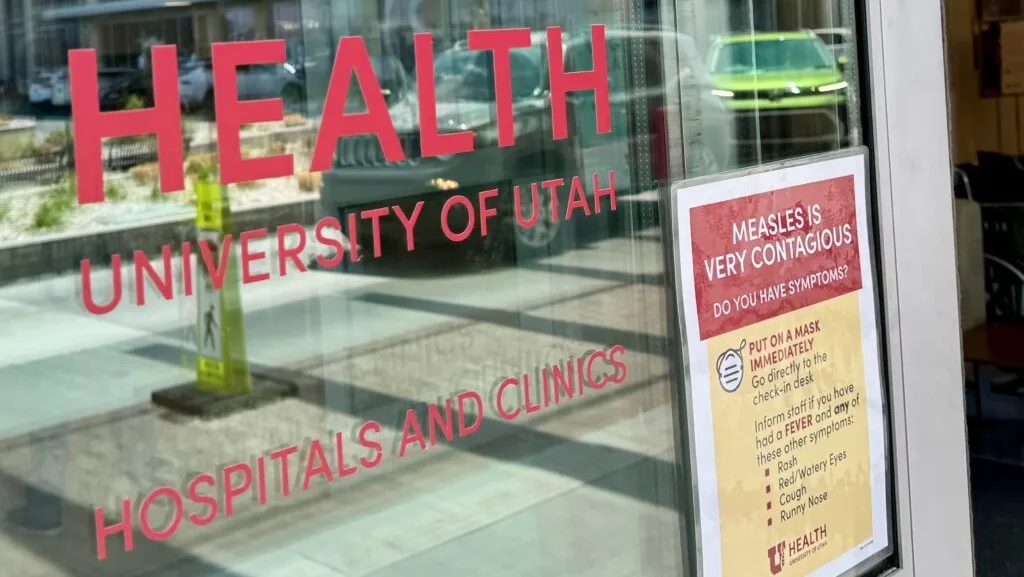

Symptoms usually start seven to 14 days after infection. They include fever, cough, runny nose, and red or watery eyes. Tiny white spots typically appear inside the mouth two to three days after symptoms begin. Three to five days after the first symptoms, a rash appears. The rash usually begins as flat, red spots at the hairline or on the face, which then spread down the body.

Many people infected with measles will experience mild symptoms, but about 1 in 5 unvaccinated people need to be hospitalized, according to health officials. Young children, pregnant women and people who have weakened immune systems are more likely to have serious problems from measles.

Vaccine recommendations vary depending on age and vaccination history

- Children should receive two doses of measles vaccine: one dose at 12 to 15 months of age and another at 4 to 6 years.

- Typically, health officials haven’t recommended early measles vaccination for all infants due to low risk — but in Washington County specifically, state officials have recommended an early, extra dose for infants who live in the area or are expected to travel there due to the high number of reported cases.

- Adults born before 1957 generally do not need to be vaccinated because they are likely already immune to measles due to widespread infection and illness before the measles vaccine became available in 1963.

- Adults who were vaccinated before 1968 should have a second dose because the vaccine used from 1963 to1967 was less effective than the current vaccine, which became available in 1968.

- Adults who were vaccinated in 1968 or later are considered fully protected whether they have one or two doses, though certain higher risk groups (like college students, health care workers and international travelers) should have two doses.

To learn whether you or your child needs a dose of the measles vaccine, health officials urge Utahns to talk to their doctors or check their immunization records. Most Utahns’ records are available through the secure Docket app or website.

This story was originally produced by Utah News Dispatch, which is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network which includes Idaho Capital Sun, and is supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity.

Idaho Capital Sun is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Idaho Capital Sun maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Christina Lords for questions: info@idahocapitalsun.com.