PULLMAN, WA — A single exposure to a toxic fungicide during pregnancy can increase the risk of disease for 20 subsequent generations — with inherited health problems worsening many generations after exposure.

Those are the findings of a new Washington State University study of rats that expands the understanding of how long the intergenerational effects of toxic exposure may last, as they are passed down through alterations in reproductive cells. The study, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was co-authored by WSU biologist Michael Skinner, who has been studying this “epigenetic transgenerational inheritance” of disease for two decades.

The research has implications for deciphering rising disease rates among humans, Skinner said, suggesting that the reason someone has cancer today may be rooted in an ancestor’s exposure to toxins decades earlier. On the other hand, epigenetics research has also unearthed potential treatments by identifying measurable biomarkers for diseases that could eventually spur preventative treatments.

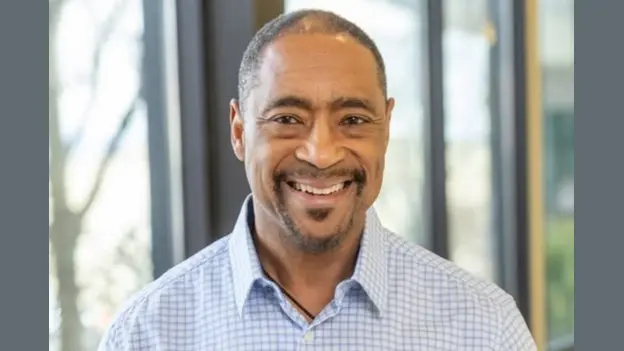

“This study really does say that this is not going to go away,” said Skinner, a professor in the School of Biological Sciences and founding director of the Center for Reproductive Biology. “We need to do something about it. We can use epigenetics to move us away from reactionary medicine and toward preventative medicine.”

The research suggests that the reason someone has cancer today may be rooted in an ancestor’s exposure to toxins decades earlier.

Skinner first identified the epigenetic inheritance of disease in 2005 and has published scores of papers since. The effects are transmitted through alterations in sperm and egg cells — the germline — and past studies have shown that the inherited disease incidence can be greater than that arising from direct exposure to toxins.

“Essentially, when a gestating female is exposed, the fetus is exposed,” he said. “And then the germline inside the fetus is also exposed. From that exposure, the offspring will have potential effects of the exposure, and the grand offspring, and it keeps going. Once it’s programmed in the germline, it’s as stable as a genetic mutation.”

Recently, Skinner’s lab has been trying to determine how long those effects last and whether the disease risk changes over the generations.

In a study published late last year, Skinner’s team looked at 10 generations of rats following an initial exposure of vinclozolin, a fungicide used primarily in fruit crops to control blight, mold and rot. The heightened prevalence of disease persisted through those generations.

The current paper, published in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences, doubled the number of generations studied, showing a similar persistence of disease in the kidneys, prostate, testes and ovaries, as well as other health effects. What’s more, starting in later generations, mothers and offspring began to die in large numbers during the birth process.

“The presence of disease was pretty much staying the same, but around the 15th generation, what we started to see was an increased disease situation,” Skinner said. “By the 16th, 17th, 18th generations, disease became very prominent and we started to see abnormalities during the birth process. Either the mother would die, or all the pups would die, so it was a really lethal sort of pathology.”

Skinner said he scaled the dosage of the toxin conservatively, at a level below what the average person might consume in their diet.

The presence of disease was pretty much staying the same, but around the 15th generation, what we started to see was an increased disease situation.

Michael Skinner, founding director

Center for Reproductive Biology

Washington State University

The paper was co-authored by Eric Nilsson, a research professor in the School of Biological Sciences; Alexandra A. Korolenko, a previous graduate student and now postdoctoral researcher at Texas Tech University who was the lead author; and Sarah De Santos, an undergraduate research assistant in the Skinner laboratory.

Skinner said epigenetic disease inheritance could help explain the rising rates of chronic disease in humans, an increase that paralleled the rising use of pesticides, fungicides and other environmental chemicals in agriculture and other industries. More than three-quarters of Americans now deal with a chronic disease such as heart disease, cancer or arthritis, and more than half have two diseases, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Research by Skinner and others has found epigenetic alterations in human germlines that correspond with mammal studies, and the increased incidence of human disease tracks with the transgenerational results found in animal studies.

The scale of the time period involved is daunting. Twenty generations in rat populations cover a few years; in human beings, it’s more like 500. With such a long stretch of time between the potential cause and effect, how might the impacts of the exposures be mitigated?

Skinner pointed to another product of epigenetic research as a possible answer: the discovery of epigenetic biomarkers that predict susceptibility to specific diseases. Developing the use of epigenetic biomarkers to drive preventative treatments in humans could offer a valuable strategy for offsetting the long-term effects.

“In humans, we’ve actually got epigenetic biomarkers for about 10 different disease susceptibilities,” he said. “It doesn’t say you have the disease now, it says 20 years from now, you’re potentially going to get this disease. There’s a whole series of preventative medicine approaches that can be taken before the disease develops to delay or prevent the disease from happening.”