OLYMPIA, WA – A controversial, court-ordered redrawing of Washington’s political maps has survived another round in a lengthy legal fight.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled this week that the revised legislative district maps, which sought to enhance the political voice of Latino voters in the Yakima Valley, “did not discriminate on the basis of race.”

In a 31-page decision issued Wednesday, the panel of three circuit judges affirmed the process followed by a lower court in penning new boundaries in central Washington, rejecting a Republican-led challenge to erase the lines and start over.

“The district court’s thoughtful attention to the details of the maps, population and voter numbers, and viable alternatives does not furnish evidence of racial predominance. Instead, it confirms that race was not the predominant factor in shaping the map,” Judge Margaret McKeown wrote in the opinion.

Wednesday’s ruling likely ensures the reworked contours of several legislative districts will remain in place for next year’s elections.

But it is unclear if it will end the legal battle, as lawyers for those seeking to overturn the maps could not be reached for comment.

Meanwhile, an attorney for Latino voters whose lawsuit forced the redrawing applauded the outcome.

The decision assures Yakima Valley’s Latino voters can “elect state legislators who best serve their community” and makes clear protections provided in the federal Voting Rights Act “should not be undermined by third parties with no skin in the game,” Simone Leeper, senior legal counsel for redistricting at Campaign Legal Center, said on Thursday.

“This victory is the result not just of this case but of decades of work by this community to secure their right to fair representation,” she said.

The state attorney general’s office, which did not defend the boundaries adopted by the Legislature or contest the judicially-redrawn map, was pleased with the outcome.

“We appreciate the court’s careful consideration of this matter,” a spokesman for Washington Attorney General Nick Brown wrote in an email. “We believe that the map ordered by the district court and used in the 2024 statewide election remedies the Voting Rights Act violation while respecting the rights of all Washington voters. We are glad to see the Ninth Circuit has agreed.”

A four-year tussle

The fight centers on a lawsuit filed by Latino voters, arguing the 15th Legislative District borders adopted by the state’s bipartisan Redistricting Commission and approved by the Washington Legislature in early 2022.

The lawsuit contended the final map violated the federal Voting Rights Act because it impaired the ability of Latino voters to participate equally in elections. The case included a trial in June 2022 featuring testimony from commissioners and voting experts.

Plaintiffs argued that while Latinos were a slight majority of the district’s voters, the final contours included areas where their turnout is historically lower and excluded communities where Latinos are more politically active.

This fracturing can depress Latino turnout and weaken their voting strength, they argued.

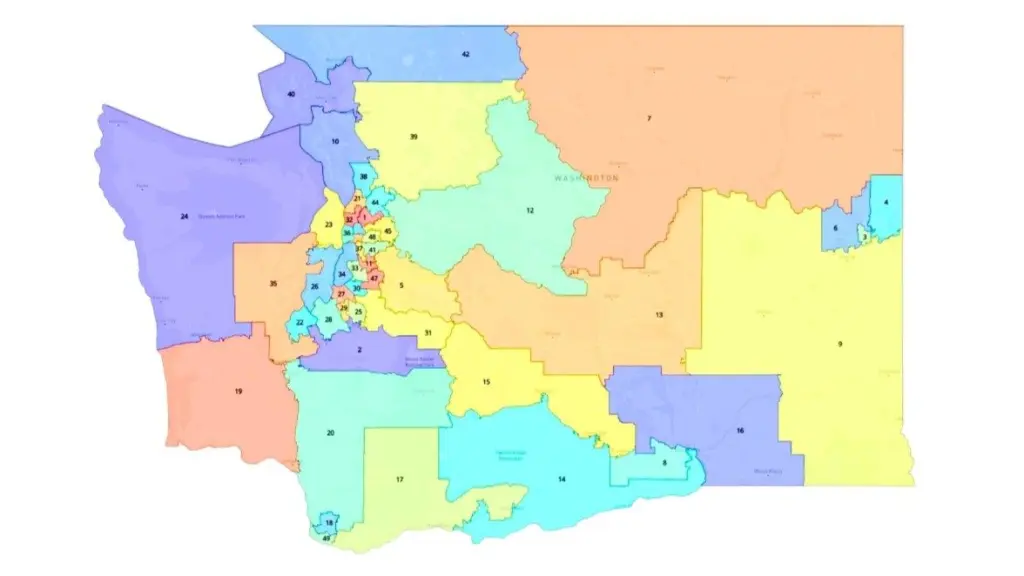

U.S. District Court Judge Robert Lasnik agreed, ruling in August 2023 that the configuration of the district diluted the Latino vote. In early 2024, Lasnik approved a new district map covering communities from East Yakima to Pasco and including Wapato, Toppenish, Grainger and Sunnyside. Nearly all of the historic lands of the Yakama Nation Reservation are in the district.

As part of the solution, he renumbered the 15th district as 14th, ensuring legislative positions, including the state Senate seat, were on ballots in presidential election years starting that year.

Plaintiffs argued that the Latino community will have a better chance to elect a candidate of their choosing in these years because that is when turnout of Latino voters is historically higher. Last November, in the first election in the redrawn district, Republican candidates won all three legislative seats.

Three registered voters — Jose Trevino, state Rep. Alex Ybarra, R-Quincy, and Ismael Campos were allowed to enter the case as intervenors.

They argued race was given too much weight in the drawing of boundaries and that the map should be redrawn with a focus on compactness and communities of interest. They also contended that the appeals court, not Lasnik, should have handled the original challenge.

A decision in three parts

The appeals court dismissed the argument that the case started out in the wrong court.

Intervenors also argued that they suffered harm as a result of the new map. On this point, the court first had to decide if each one had standing to make the argument. Judges decided one did and two didn’t.

Trevino could because he is the only one who lived in the old 15th district and wound up in the newly drawn 14th. However, they said he would not see his vote diluted “merely because he is Hispanic and will now vote alongside fewer Hispanics.”

But for the three Intervenors, the primary target was the map approved by Lasnik. They asserted it is an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. To prove that, they had to show that race was the predominant factor in Lasnik’s decision on where to draw the lines.

The appeals court judges said there was no evidence that this was the case and, as McKeown wrote, that nothing in the court record “supports a claim that race predominated in the redistricting process.”.

Opponents also argued that too many Washingtonians were moved into new districts, that the new partisan composition favors Democrats, and that incumbents were harmed as a result.

Lasnik redrew boundaries for 13 legislative districts across 12 counties in central and southwest Washington, and the Puget Sound region. More than 500,000 voters wound up in new districts, state election officials said. Five Republican legislators found themselves in new districts while no Democratic lawmakers were displaced.

Judges said those arguments “are objections based on partisanship, not race,” and not relevant.

Joining McKeown in the opinion were Judges Ronald Gould and John B. Owens. All three were appointed by Democratic presidents, two by Bill Clinton and one by Barack Obama.

This story first appeared on Washington State Standard.